BY KENT SHAW, CFA

In 1952, Patti Page sang How Much is That Doggie in the Window? The song later rushed up the Billboard music charts to number one in 1953. Clearly, those were wild times. The title of this quarter’s Deeper Dive section is a parody of that song title. In this short piece, we will take a look at price transparency in healthcare, which is almost nonexistent, and the potential effects of increased transparency. Improving transparency could offer many benefits but there are also a number of obstacles to such an effort.

Imagine this scenario: you sit down to a nice dinner with your family at a restaurant highly recommended by a dear friend. The menu is quite impressive and you are already pleased with your decision to dine there. However, you’re puzzled to discover that there are no prices on the menu. Apparently none of your family members have prices on their menus either. When you inquire about this oddity with the waiter, he replies that they will send you a bill 30 to 90 days after you dine there. In addition to what you order, the ultimate cost will depend on whether or not the restaurant is in your network and how long you stay at the table. Your friend mentioned that the prices were reasonable but you don’t know whether he was “in network” or not. The waiter assures you that you shouldn’t worry because the price won’t vary more than 400% and the average check range is just $100-500 for a family your size. Suddenly you’ve lost your appetite and you begin wondering if there are any boxes of ‘mac and cheese’ in the pantry at home.

The example above is a direct reflection of how the majority of people in the US experience healthcare costs. In contrast, regulations in finance require that banks disclose the amount of principal and interest that a homeowner will pay over the life of a mortgage before they sign the document. Some disclosure of potential costs for medical treatment should be equally as important, recognizing that it is impossible to know the exact cost before an episode of care begins. The West Health Policy Center released a study in 2014 showing that greater price transparency could reduce overall healthcare costs by $10B per year. In 2014, total healthcare spending was $3 trillion or roughly 18% of total US GDP. Saving $10B sounds impressive until it is compared to these numbers but other studies show the savings could be far greater once economic forces are allowed to respond.

High deductible healthcare plans (HDHPs) were far less common 10 years ago but now represent more than 40% of private insurance plans, according to Strategas research. Such plans offer a lower premium along with a higher deductible and a health savings account. Each year, money can be added to the health savings account without being taxed, up to certain limits, and any money not spent can be used in subsequent years and even invested if desired. Research has shown that consumers with HDHPs use fewer healthcare services than those with conventional plans that offer a co-pay and lower deductible. Choosing between healthcare providers, however, is difficult when pricing and quality information are unavailable.

There is no doubt that price impacts behavior as shown by the HDHP usage data. On the other end of the spectrum we see unintended consequences can be costly. One of the main goals of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was to bring health insurance to lower income individuals that could not afford insurance. Before the ACA was passed, a large portion of these uninsured people visited emergency rooms for care because the law requires that everyone be treated in such a setting regardless of their ability to pay. In 2008, a study of lower income Medicaid patients in Oregon showed they were 40% more likely to use the emergency room for care than their uninsured counterparts even though they had free care from a primary care physician. The majority of the conditions treated in these settings were non-urgent and could have been treated effectively in less costly environments such as a low cost clinic at a drug store or at a primary care physician. The Medicaid insureds acted rationally though; they had no personal incentive to seek care in a setting that would cost Medicaid less money. Is it possible that a small co-pay, perhaps $20-40 for emergency room visits would solve the problem of lower income patients seeking non-emergency care in this expensive setting while still providing healthcare access? This idea may be worth pursuing, but the Department of Health and Human Services reported that spending for emergency room care was only 2% of total US healthcare spending in 2014 so larger areas would need to be targeted to effectively reduce total spending.

While pricing before a health event is difficult to obtain, consumers generally view price as an indication of quality in the absence of other information. We assume a higher priced car is higher quality than a lower priced car, a more expensive restaurant is better than a less expensive one, etc. In many cases this is true but healthcare can be a large exception. In 2010, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) conducted a study that evaluated the cost and quality of hip and knee replacements for its members. Data showed that costs ranged from $15,000 to $110,000 with no discernable link between cost and quality. CalPERS responded by setting a rate of $30,000 for such procedures after determining that a large number of high quality facilities with high procedure volume charged less than this amount. Employees seeking this procedure were allowed to use facilities that charged more than this reference price but they would be responsible for any amount above $30,000. Over the two year study period, CalPERS saved $5.5 million or an average of $9,000 per procedure (a 26% decline) and outcomes were similar or better than those not in the study. Facilities in the area that charged above the reference rate began lowering their prices. In this case, CalPERS had data and purchasing power that could be used for the advantage of its members but healthcare pricing and quality data are often scarce for the average consumer. Pricing data from other sources show that the costs for services vary widely in other areas as well. As an example, data from New Choice Health shows that prices for an ankle MRI in Atlanta can range from $400 to $1050, a range of almost 300%.

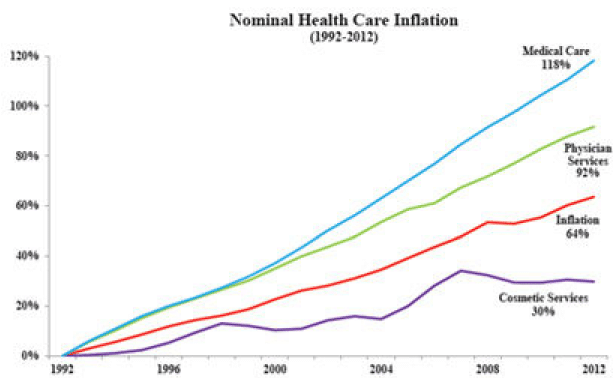

The basis of economics is the notion that individuals respond to incentives. Sometimes these incentives are financial and in other cases they are more qualitative. Businesses also respond to incentives often lowering prices in order to gain more customers and keep existing ones. We can see these forces at work in other areas of healthcare where insurance is not present. Cosmetic health services including various cosmetic surgeries and skin treatments have increased far less than overall healthcare costs. According to data from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, the cost for the top 5 cosmetic surgical procedures in 2015 had increased in cost by an average of 23% since 1998, well below the overall increase in healthcare costs of 92% over the same period. The nearby chart illustrates some of this data. LASIK eye surgery cost roughly $2500 per eye when the procedure began in volume in 1999. Since that time costs have fluctuated but are now 10-15% lower with an improved procedure and greater patient satisfaction. LASIK is generally not covered by health insurance.

There is enough evidence to suggest that making pricing and quality information for healthcare service available to consumers would likely reduce overall spending while outcomes may be unaffected. Some of the barriers to such efforts include insurance contracts with providers that prohibit disclosing pricing information. Other issues include difficulty in determining what services a patient will need in advance, the lack of standard formatting for reporting prices, and difficulties that arise when more than one provider participates in an episode of care. However, none of these barriers appear insurmountable. Some insurance companies have already begun providing pricing and subjective quality ratings for providers within their networks but most consumers are unaware of the data. Web-based services such as Healthcare Bluebook and New Choice Health offer price data for consumers so they can make more informed decisions but objective data on quality is still largely absent.

We are unsure how quickly these changes will impact the healthcare industry but there will be winners and losers. It is fair to say that the segments which consume the largest portion of healthcare dollars are most at risk. Primary care physicians consume a relatively small part of healthcare (10% or less) while hospitals consume much more. We will continue to watch the sector closely and assume that the future is unlikely to be a continuation of the past.