Can we capture international exposure with domestic equities, and if so should we?

BY BRENDAN WAGNER, Portfolio Manager

How much international exposure should a US investor have in an equity portfolio? With 75% of global economic activity occurring outside the US, some investors consider it irresponsible NOT to have international stock exposure. About 44% of S&P500 constituents’ revenues are already coming from outside the US, so even without owning international stock directly, a US investor has significant exposure to what happens abroad.

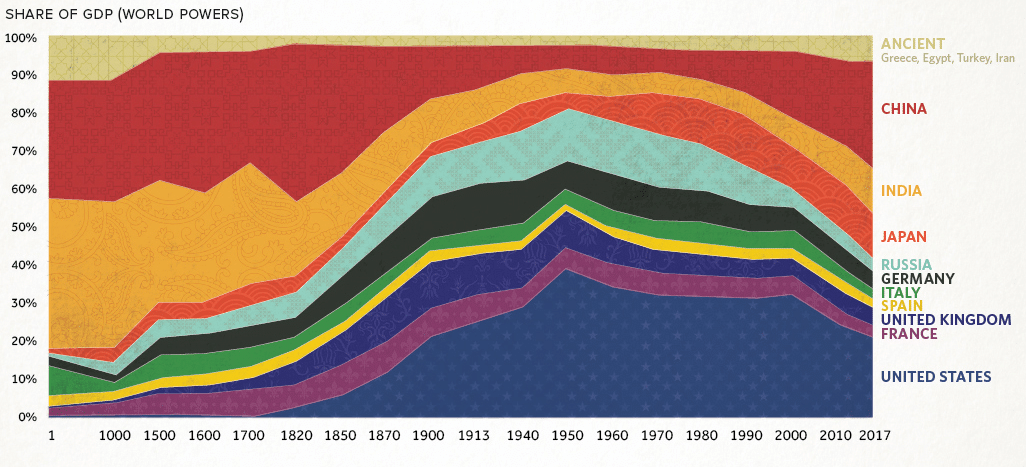

When considering how to achieve international exposure, remember that Gross Domestic Product comprises much more than the economic activity of publicly traded companies. In the US and abroad, it includes the Postal Service, Federal and municipal government spending, university and hospital spending, etc. Large parts of a country’s GDP are unavailable for public market participants, and that’s not a bad thing unless one thinks they’re missing out by not losing money with Amtrak or the DMV. I bring this up to get us thinking about what is “investable” for us outside the US. Our country is about as privatized as they get, so a larger share of other nations’ economic activity is actually government run, and uninvestable. A domestic-only strategy might be “passing” on 75% of global GDP but only 40% of “investable” global GDP. Even considering investable International GDP, are you missing out by not owning state-controlled Chinese banks? The newly-public Aramco in Saudi Arabia? Gazprom, the majority state-owned gas behemoth in squeaky-clean Russia? Pemex (the government’s piggy bank) in Mexico or Petroleos de Venezuela? One ought to be choosy when considering their international exposure.

But I digress. What I am curious about in this blog post is whether a US investor could achieve similar exposures and performance using domestic stocks as they could achieve by reducing US exposure and buying international stocks.

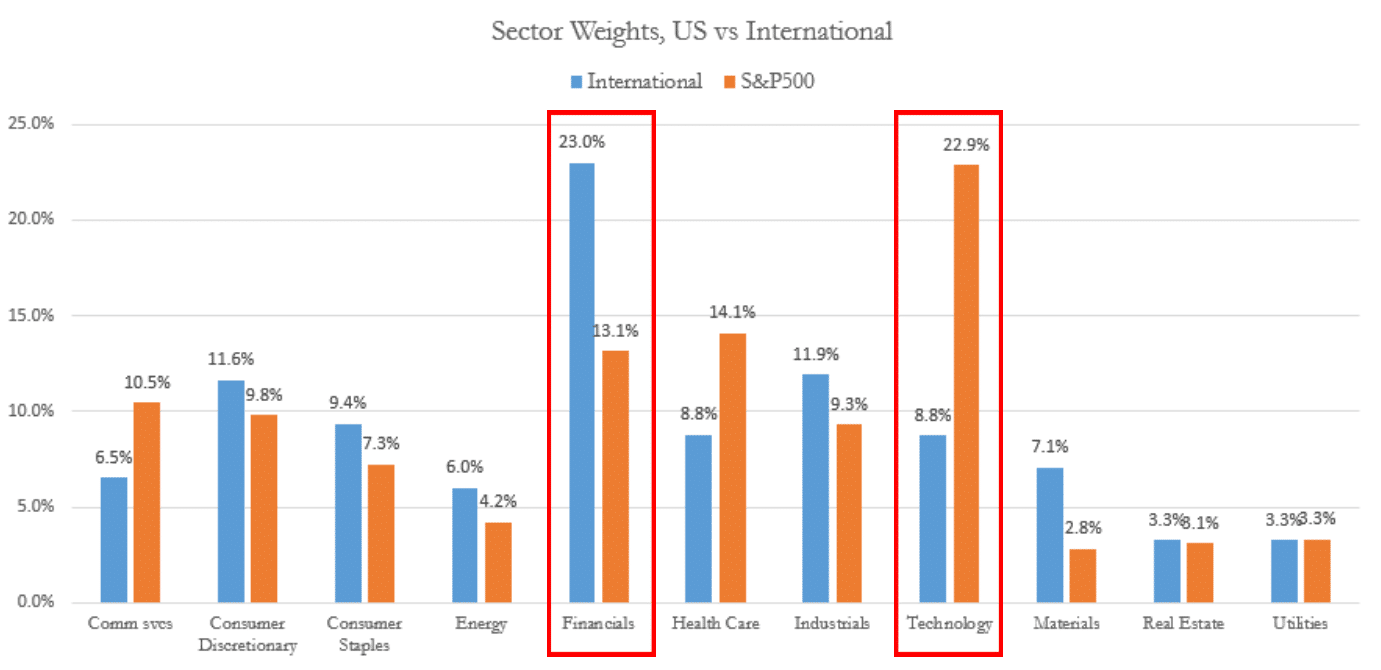

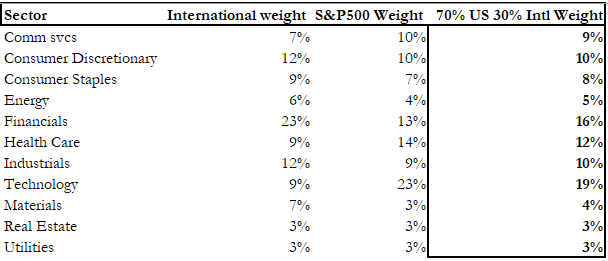

One thing I want to highlight is an overlooked feature of the “US vs International” exposure discussion. Specifically, it’s really more of a sector bet or “value versus growth” bet, than any major geographical bet. It largely comes down to two sectors and their respective weights in the indices. Financials are 23% of the international index vs 13% in the US, and technology is just 9% of the international index versus 23% in the US.

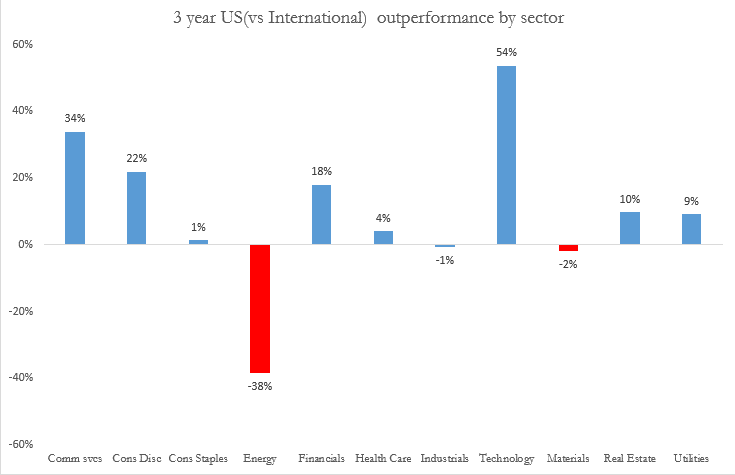

The ACWI ex-US index has returned 33% over the past 3 years, significantly trailing the SP500’s return of 52%. Below is a look at the US performance vs International by sector. US Energy trailed, but at such a small weight in the index this did not hold the US back. In Technology, the 54% outperformance by US stocks was in a sector in which these stocks are also hugely overweight versus international, as we saw above. A double whammy for International.

The most evenly-matched race was in consumer staples, because Nestle, Diageo and the like are formidable competition for Pepsi and Procter & Gamble. International semiconductor companies such as Taiwan Semi and Samsung offer fine competition for Intel, Texas Instruments and Analog Devices. On the other hand, International Financials have been no match for peers in the US for a variety of reasons, including state control in China and negative interest rates in Europe.

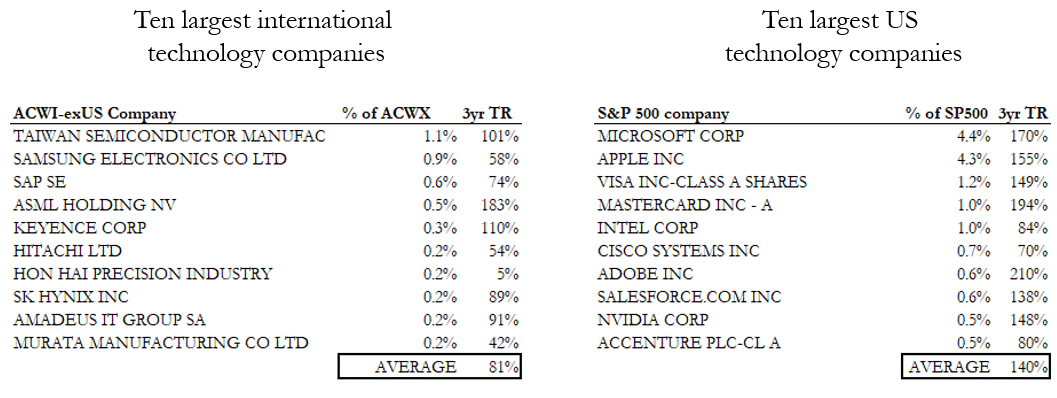

Technology is the sector where it’s been a real bloodbath in terms of US outperformance versus international. Note the top ten tech companies in the ACWI Ex-US vs those on the right in the S&P500. USA ahead by 60% but that only tells part of the story. These ten US stocks have a combined weight of 15% of the SP500 while their international peers comprise only 4% of their index, meaning international tech stocks’ impressive performance was not weighted heavily enough to help the ACWI Ex-US.

Why such outperformance by US companies? There are dozens of reasons but I’ll cite a few possibilities. Within sectors, there are often much more dynamic companies in the US. It could be a function of the US being friendlier to wealth creation, as well as an antitrust position that focuses more on what’s best for the consumer rather than what is best for competition within an industry. US companies have embraced the “Bain-McKinsey Bible” of lean and efficient operating principles, at least a bit more so than European companies. I do not say that as a blanket positive of course, considering that efficiency gains necessitate sharing less profit with employees. Consider the exasperated response former Nestle Chairman Peter Brabeck gave when analysts were aggressively pushing him to cut what they considered bloated spending:

“Look, Europe is not the United States; we operate largely in Europe. What do you want from me … to go through the organization with a ‘machine gun’?”

The machine-gun comment was of course not about actual violence, but about slashing expenses for the benefit of near term financial results. And to be fair, European companies may operate with a bit more concern for their employees’ quality of life.

So, US or International? It really seems to offer up some interesting choices in how one gains sector exposure. If one were to go the traditional route of simply reducing their S&P500 exposure while adding ACWI ex-US, here’s how the sector shift would look if one went from 100% US to a combination of 70% US and 30% International.

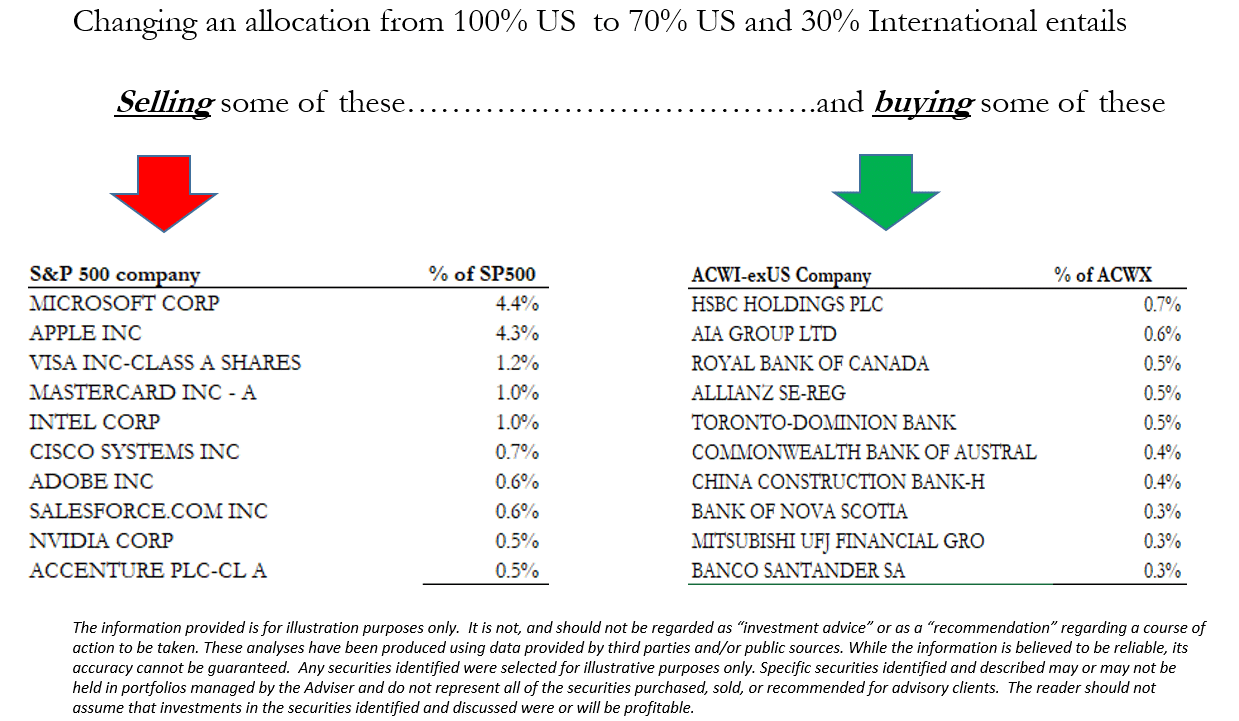

In practice, this would involve selling US tech shares, and putting those funds into international financials:

Now, had one done that three years ago, it would have been a severe drag on performance – that’s backward looking, but these weights were similar back then and the differences in business quality and growth prospects were much the same. What’s entirely possible of course, is for those big expensive US tech darlings to see significant PE compression in coming years, while the unloved international financials reawaken and gain a couple points of PE.

If one were to prefer the overall characteristics of US companies (shareholder friendly, generally more efficient from a cost standpoint) but also attain the global diversification of a 70% US and 30% International portfolio, you could get largely there by pulling some of the proceeds from your reduced US tech position into US financials instead of international financials. Still though, the timing could be wrong if the international central banker community wakes up and realizes negative interest rates are destroying their banking industries. The international banks’ discount to US banks could disappear and make one wish they’d gone with international rather than US banks.

But one thing we need to keep in mind is that while many international companies have not employed the “Bain/McKinsey Bible,” or the movement toward lean operations, the possibility (and share price upside) is there for them to unlock that value. How one achieves international exposure is a topic we have just touched the surface of today. One thing does seem to make sense – go international for exposure where the companies and sectors are as well run, and have as good a fighting chance, as their US peers.